Students will be engaged individually in primary source analysis and use collaborative teaming to make use of the knowledge gained by presenting the findings of their research to the rest of the class. Finally, the student will have the opportunity to review the work of peers and to have their work reviewed in a team setting.

This lesson prepares students to use primary sources for research purposes. It provides students the opportunity to work on their analysis and research skills, their presentation skills (both creating and delivering), and the opportunity to participate in peer review of others’ work.

The student will analyze a primary document by filling out the “Read Like a Historian” matrix with at least 80% accuracy. As a team, the students will produce a poster describing and summarizing the content and historical significance of their documents with at least 80% accuracy. And, finally, each team will present their findings to the entire class.

Common Core Anchors:

- Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development, summarize the key supporting details and ideas.

- Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical , connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape the meaning or tone.

Missouri State GLEs for Middle School Social Studies:

- Select, investigate, and present a topic using primary and secondary resources, such as oral interviews, artifacts, journals, documents, photos, and letters. TS7A (DOK4)

- Create maps, graphs, timelines, charts and diagrams to communicate information. TS7Bb (DOK2)

- Identify, research, and defend a point of view/position. TS7G

- “Read like a Historian” matrix, modified as middle level reading activity

- Context Handouts

- Poster sized Post-it Notes

- Magic Markers

Ideally, all of the photographs and illustrations would also be printed for the team to accompany the four textual sources that will be read and analyzed.

- Set One: Child Labor http://www.eiu.edu/eiutps/Childhood%20Lost%20Primary%20Source%20Set.pdf

Pages 11, 12, 15, 16

- Set Two: The De Priest Incident

DePriest Tea Incident

- Set Three: Human Rights

Pages 1, 4

http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2009-12-14/pdf/E9-29865.pdf

http://www.marxists.org/history/usa/workers/black-panthers/1966/10/15.htm

- Set Four: Desegregation of the Military

https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/online-collections/desegregation-of-armed-forces

- Set Five: Internment of the Issei and Nisei

Child Labor

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, power-driven machines replaced hand labor for making most manufactured items. Factories began to spring up everywhere, first in England and then in the United States. The factory owners found a new source of labor to run their machines—children. Operating the power-driven machines did not require adult strength, and children could be hired more cheaply than adults. By the mid-1800’s, child labor was a major problem.

Children had always worked, especially in farming. But factory work was hard. A child with a factory job might work 12 to 18 hours a day, six days a week, to earn a dollar. Many children began working before the age of 7, tending machines in spinning mills or hauling heavy loads. The factories were often damp, dark, and dirty. Some children worked underground, in coal mines. The working children had no time to play or go to school, and little time to rest. They often became ill.

By 1810, about 2 million school-age children were working 50- to 70-hour weeks. Most came from poor families. When parents could not support their children, they sometimes turned them over to a mill or factory owner. One glass factory in Massachusetts was fenced with barbed wire "to keep the young imps inside." These were boys under 12 who carried loads of hot glass all night for a wage of 40 cents to $1.10 per night.

Church and labor groups, teachers, and many other people were outraged by such cruelty. The English writer Charles Dickens helped publicize the evils of child labor with his novel Oliver Twist.

Britain was the first to pass laws regulating child labor. From 1802 to 1878, a series of laws gradually shortened the working hours, improved the conditions, and raised the age at which children could work. Other European countries adopted similar laws.

In the United States it took many years to outlaw child labor. By 1899, 28 states had passed laws regulating child labor. Many efforts were made to pass a national child labor law. The U.S. Congress passed two laws, in 1918 and 1922, but the Supreme Court declared both unconstitutional. In 1924, Congress proposed a constitutional amendment prohibiting child labor, but the states did not ratify it. Then, in 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act. It fixed minimum ages of 16 for work during school hours, 14 for certain jobs after school, and 18 for dangerous work. Today all the states and the U.S. government have laws regulating child labor. These laws have cured the worst evils of children working in factories.

Source: http://www.scholastic.com/teachers/article/history-child-labor

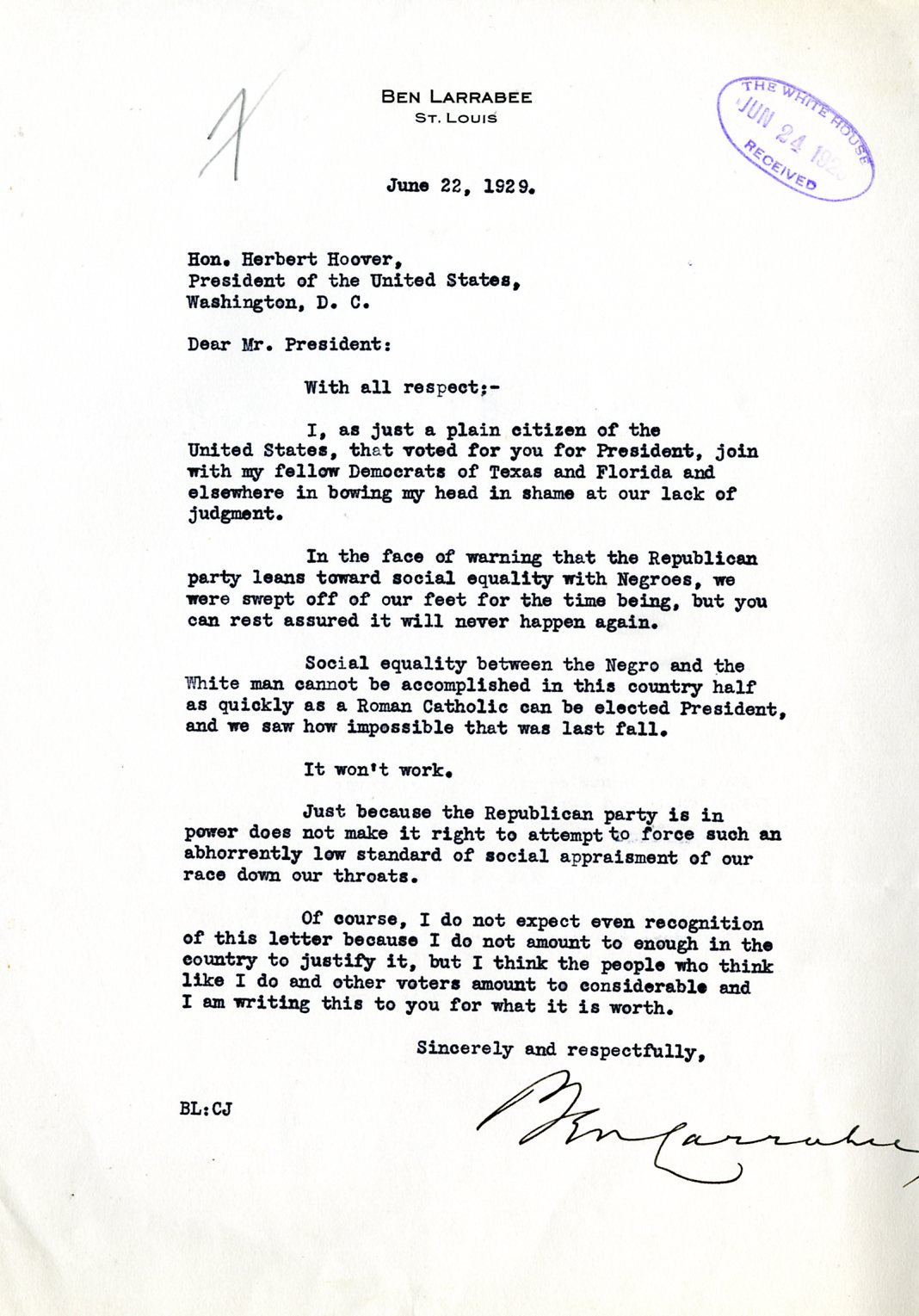

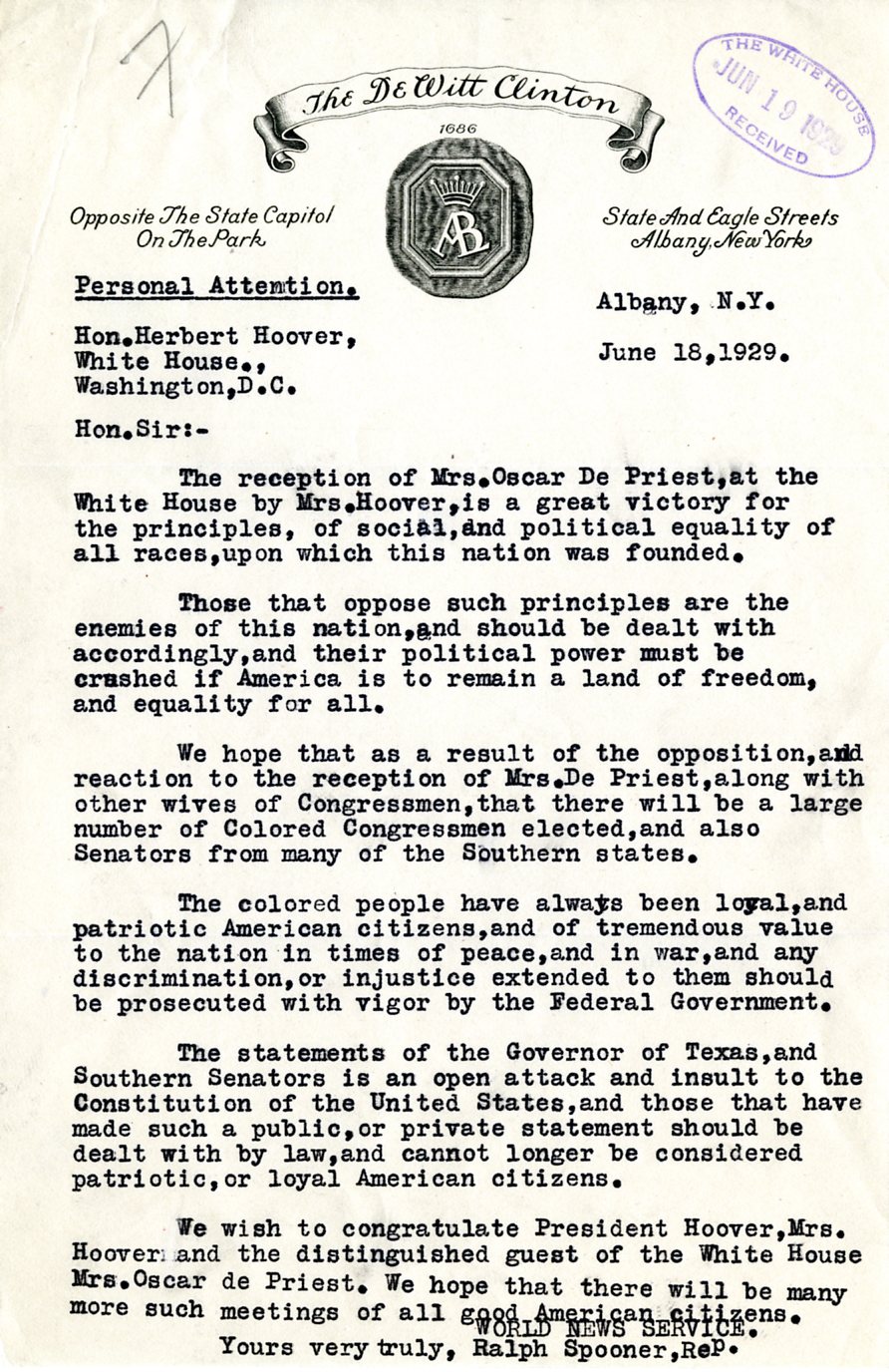

De Priest Incident

‘A Tempest in a Teapot’

The Racial Politics of First Lady Lou Hoover’s Invitation of Jessie DePriest to a White House Tea

First Lady Lou Hoover’s invitation to Jessie L. DePriest to a White House tea party in 1929 created a storm of protest and indignation. This traditional act of hospitality toward the wife of the first black elected to Congress in the twentieth century created a political crisis for the president and first lady.

This presentation examines the “tempest” from the perspectives of the first lady, the DePriests, and DePriest family descendants.

The story of Oscar and Jessie DePriest highlights the courage and contributions of Oscar Stanton DePriest, the sole black voice in Congress at that time, to the history of the American civil rights struggle and the grace and poise of his wife who ably represented a generation of black women.

Source: http://www.whitehousehistory.org/presentations/depriest-tea-incident/index.html

Human rights are moral principles that set out certain standards of human behavior, and are regularly protected as legal rights in national and international law They are "commonly understood as inalienable fundamental rights to which a person is inherently entitled simply because she or he is a human being." Human rights are thus conceived as universal (applicable everywhere) and egalitarian (the same for everyone). The doctrine of human rights has been highly influential within international law, global and regional institutions. Policies of states and in the activities of non-governmental organizations and have become a cornerstone of public policy around the world. The idea of human rights suggests, "if the public discourse of peacetime global society can be said to have a common moral language, it is that of human rights." The strong claims made by the doctrine of human rights continue to provoke considerable skepticism and debates about the content, nature and justifications of human rights to this day. Indeed, the question of what is meant by a "right" is itself controversial and the subject of continued philosophical debate.

Many of the basic ideas that animated the human rights movement developed in the aftermath of the Second World War and the atrocities of The Holocaust, culminating in the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Paris by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948. The ancient world did not possess the concept of universal human rights The true forerunner of human rights discourse was the concept of natural rights which appeared as part of the medieval Natural law tradition that became prominent during the Enlightenment with such philosophers as John Locke, Francis Hutcheson, and Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui, and featured prominently in the English Bill of Rights and the political discourse of the American Revolution and the French Revolution.

From this foundation, the modern human rights arguments emerged over the latter half of the twentieth century

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_rights

Desegregation of the Military

In 1940 the U.S. population was about 131 million, 12.6 million of which was African American, or about 10 percent of the total population. During World War II, the Army had become the nation’s largest minority employer. Of the 2.5 million African Americans males who registered for the draft through December 31, 1945, more than one million were inducted into the armed forces. African Americans, who constituted approximately 11 per cent of all registrants liable for service, furnished approximately this proportion of the inductees in all branches of the service except the Marine Corps. Along with thousands of black women, these inductees served in all branches of service and in all Theaters of Operations during World War II.

During World War II, President Roosevelt had responded to complaints about discrimination at home against African Americans by issuing Executive Order 8802 in June 1941, directing that blacks be accepted into job-training programs in defense plants, forbidding discrimination by defense contractors, and establishing a Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC).

After the war, President Harry Truman, Roosevelt’s successor, faced a multitude of problems and allowed Congress to terminate the FEPC. However, in December 1946, Truman appointed a distinguished panel to serve as the President’s Commission on Civil Rights, which recommended "more adequate means and procedures for the protection of the civil rights of the people of the United States." When the commission issued its report, "To Secure These Rights," in October 1947, among its proposals were anti-lynching and anti-poll tax laws, a permanent FEPC, and strengthening the civil rights division of the Department of Justice.

In February 1948 President Truman called on Congress to enact all of these recommendations. When Southern Senators immediately threatened a filibuster, Truman moved ahead on civil rights by using his executive powers. Among other things, Truman bolstered the civil rights division, appointed the first African American judge to the Federal bench, named several other African Americans to high-ranking administration positions, and most important, on July 26, 1948, he issued an executive order abolishing segregation in the armed forces and ordering full integration of all the services. Executive Order 9981 stated that "there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed forces without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin." The order also established an advisory committee to examine the rules, practices, and procedures of the armed services and recommend ways to make desegregation a reality. There was considerable resistance to the executive order from the military, but by the end of the Korean conflict, almost all the military was integrated.

Source: http://www.ourdocuments.gov/print_friendly.php?flash=true&page=&doc=84&title=Executive+Order+9981%3A+Desegregation+of+the+Armed+Forces+%281948%29

Issei and Nisei

Over 127,000 United States citizens were imprisoned during World War II. Their crime? Being of Japanese ancestry.

Despite the lack of any concrete evidence, Japanese Americans were suspected of remaining loyal to their ancestral land. Anti-Japanese paranoia increased because of a large Japanese presence on the West Coast. In the event of a Japanese invasion of the American mainland, Japanese Americans were feared as a security risk.

Succumbing to bad advice and popular opinion, President Roosevelt signed an executive order in February 1942 ordering the relocation of all Americans of Japanese ancestry to concentration camps in the interior of the United States.

Evacuation orders were posted in Japanese-Americans communities giving instructions on how to comply with the executive order. Many families sold their homes, their stores, and most of their assets. They could not be certain their homes and livelihoods would still be there upon their return. Because of the mad rush to sell, properties and inventories were often sold at a fraction of their true value.

After being forced from their communities, Japanese families made these military style barracks their homes.

Until the camps were completed, many of the evacuees were held in temporary centers, such as stables at local racetracks. Almost two-thirds of the interns were NISEI, or Japanese Americans born in the United States. It made no difference that many had never even been to Japan. Even Japanese-American veterans of World War I were forced to leave their homes.

Ten camps were finally completed in remote areas of seven western states. Housing was Spartan, consisting mainly of tarpaper barracks. Families dined together at communal mess halls, and children were expected to attend school. Adults had the option of working for a salary of $5 per day. The United States government hoped that the interns could make the camps self-sufficient by farming to produce food. But cultivation on arid soil was quite a challenge.

Source: http://www.ushistory.org/us/51e.asp

Engagement:

(5-10 minutes)

Teacher leads a whole class discussion on: “What is a Source?” As the students offer ideas on what constitutes a source, the teacher writes “Primary” and “Secondary” on the board and sorts the student responses into the appropriate list.

Teacher then asks: “Why do we Cite our Sources when we do research?”

If necessary, teacher gives a brief description of plagiarism and why it must be avoided in all research.

Lesson Procedure:

(60-70 minutes)

With students in groups of four, pass out a Read Like a Historian handout for each student, a historical background or context handout, and a set of four primary source documents on a single topic for each team. (5 minutes)

Instruct students to each select one of the primary source documents, read and annotate it, then answer the questions on Sourcing, Contextualization, and Close Reading individually on their own document and the questions on Corroboration as a team for all four documents. (25 minutes)

When students have finished their document analysis, give each team a poster-sized, Post-It Note and some markers. Instruct each team to make a poster to present to the other teams that describes each document and summarizes their meaning. (20 minutes)

Have each team read out their research findings to the other teams. After each presentation, each student will write out “Two Stars and a Wish,” two things that were done well and one thing that they “wish” the team had done more of or had done better or differently. Teacher calls on one or two students to share their Two Stars and a Wish after each presentation. (20 minutes) This may be written on the back of the “Read Like A Historian” handout to save paper.

Closure:

As an exit slip, students will write out their definition of a primary source and their definition of plagiarism. (5-10 minutes) This may be written on the back of the “Read Like A Historian” handout to save paper.

Adaptations and Modifications:

- Students may use any adaptive technology (braille readers, tape recorders, word processing programs, etc.) to access the documents.

- Students struggling with reading may be paired with a study buddy who is willing and able to help them during the reading portion of the lesson.

- Students struggling with writing can draw illustrations on the poster or handout to express their knowledge.

- Students needing extra time and support can take the document and handout home the night before.

- More students may be added to groups or groups may be added or eliminated to accommodate various class sizes.

|

Historical Reading Skill |

Questions |

Answers |

|

Sourcing (Before Reading the Document) |

A) What is the Author’s point of view? B) Why was it written? C) When was it written? D) Is the source believable? Why or why not?

|

|

|

Contextualization (Setting the Scene) |

E) What else was going on at the time this was written? F) What things were different back then? G) What things were the same? |

|

|

Close Reading |

H) What claims does the author make? I) What evidence does the author use to support those claims? J) How does this document make you feel? K) What words or phrases does the author use to convince me that she/he is right? L) What information does the author leave out? |

|

|

Corroboration (Finding supporting evidence) |

M) What do the other pieces of evidence say? N) What evidence is most believable?

|

|

Read Like an Historian Name:________________________

The individual student document for “Read Like a Historian” will serve as assessment of the student’s ability to read, contextualize, and corroborate a set of primary sources. The document contains sixteen questions, each worth two points for a total of 32 points.

The documents will be graded on the following characteristics:

|

No answer or a wrong answer |

Partial answer |

Complete answer |

|

0 points |

1 point |

2 points |

Each team member will receive the same grade for their poster. The poster has five elements: the four primary sources and overall presentation, each worth 5 points for a total of 25 points.

The posters will be graded on the following characteristics:

|

Primary Source Not Mentioned |

Name of Primary Source Only |

Name and Description of Primary Source |

|

0 points |

2 points |

5 points |

|

Poorly Organized or Confusing Presentation |

Complete and Interesting Presentation |

|

0 - 1 points |

2 - 5 points |

Each student will receive 0 – 13 points for their participation in the creation of the poster and in the delivery of the presentation.

Total Possible Points = 70