Why Inquire?

What happens if, by the act of historical imagination — the historian’s and our own — we are transported into the documented re-created moment of the past and, in a double vision, see the problems and values of the moment and those of our own, set against each other in mutual criticism and clarification?

History cannot give us a program for the future, but it can give us a fuller understanding of ourselves, and of our common humanity, so that we can better face the future.”

- Robert Penn Warren

In discussing the legacy of the Civil War, the author Robert Penn Warren felt compelled to capture both the value and limits of studying history. It is not, he noted, “a program for the future” because the present will never have exactly the same context as another moment in the past. History is also not a collection of facts, names, and dates as it is so often taught. The value of studying history is in studying a topic in order to answer an authentic question. Good inquiries dive into decisions or events of enduring significance allowing us to determine their impact and legacy and even to wonder: “what if?” Then, because history echoes throughout the ages, we can analyze these lessons for clues about the problems of today.

Presidential Inquiry

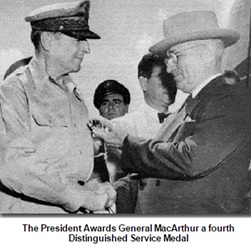

In October of 1950 Harry Truman traveled across the Pacific Ocean to meet with General MacArthur to discuss the course and conduct of the Korean War. Truman was quick to answer critics who wondered about the true purpose of this visit as Truman shared in an October 17 address in San Francisco 2:

A little later in his address, Truman clarified the purpose of this conversation even further:

Truman later felt compelled to fire General MacArthur for breaching this trust between a general and the Commander-In-Chief. Going to the original source allows us to see that there isn’t any daylight between what Truman said and what he did. If an individual were to study Harry Truman he or she would find a man of incredible candor. That quality likely explains why Truman quotes continue to pepper the speeches of political figures and why his legacy has grown over time.

Truman occupied the White House at a crucial moment in history. Picking up the reins from Franklin Roosevelt, he presided over crucial decisions that shaped the course of the modern world. His policy of containment involved the United States in world affairs to an extent never seen before. The Korean War itself was far away from home over a threat that did not directly impact the homeland. Questions relevant to this conflict continue to plague us today. Among them:

- “Are limited wars possible?”

- “What if another general had been Supreme Commander in Korea?”

- “Was Truman right to fire MacArthur?”

The Classroom

Historians practice their craft by asking questions about the past, then search for evidence to construct the best answer possible. Similarly we learn history best by asking questions about the past, going to the original sources of history and evaluating what they tell us. The lessons included on this site do just that. They pose a question connected to Truman’s time as president then direct the learner to carefully consider what the evidence reveals.

The instructional sequence is intended to be flexible; instead of attempting to lay out what to do during single class periods, these lessons are designed to encourage the steps basic to every inquiry:

- Frame the inquiry - Decide what is worthy of investigation and how it will be accomplished.

- Go to the sources - Look for reliable sources on the topic, taking note of the diverse perspectives they reveal.

- Review the evidence - Evaluate the evidence to determine what answer or interpretation is best supported by this information.

- Communicate an answer - Share the best answer or interpretation to the original question in an interesting format.

We invite you to try out these lessons and even try creating your own. You can mix up these lessons to fit the needs of your students or the time constraints of your classroom. If the documents you find don’t satisfy your students’ curiosity, you will find that many of the valuable documents held by the Truman Library are digitized. Many of these are found in research files, organized by subject, or you can dig deeper with other archival finding aids.

1 Warren, Robert Penn. The Legacy of the Civil War: Meditations on the Centennial. New York: Random House, 1961. Print

2 /calendar/travel_log/key1947/wake1950_toc.htm